Industry analysts are watching Environmental Social Governance (ESG) scores closely.

While many see them as an important stepping stone in reaching net-zero targets, others vehemently cite them as fuelling company greenwashing, adding to the climate problem.

Interest in conscious investment has risen. In the UK alone, the market’s forecast growth is 173% by 2027, according to KPMG.

Globally, millennials were twice as likely as older generations to want their pension to be invested responsibly, while 49% make investments based on social factors.

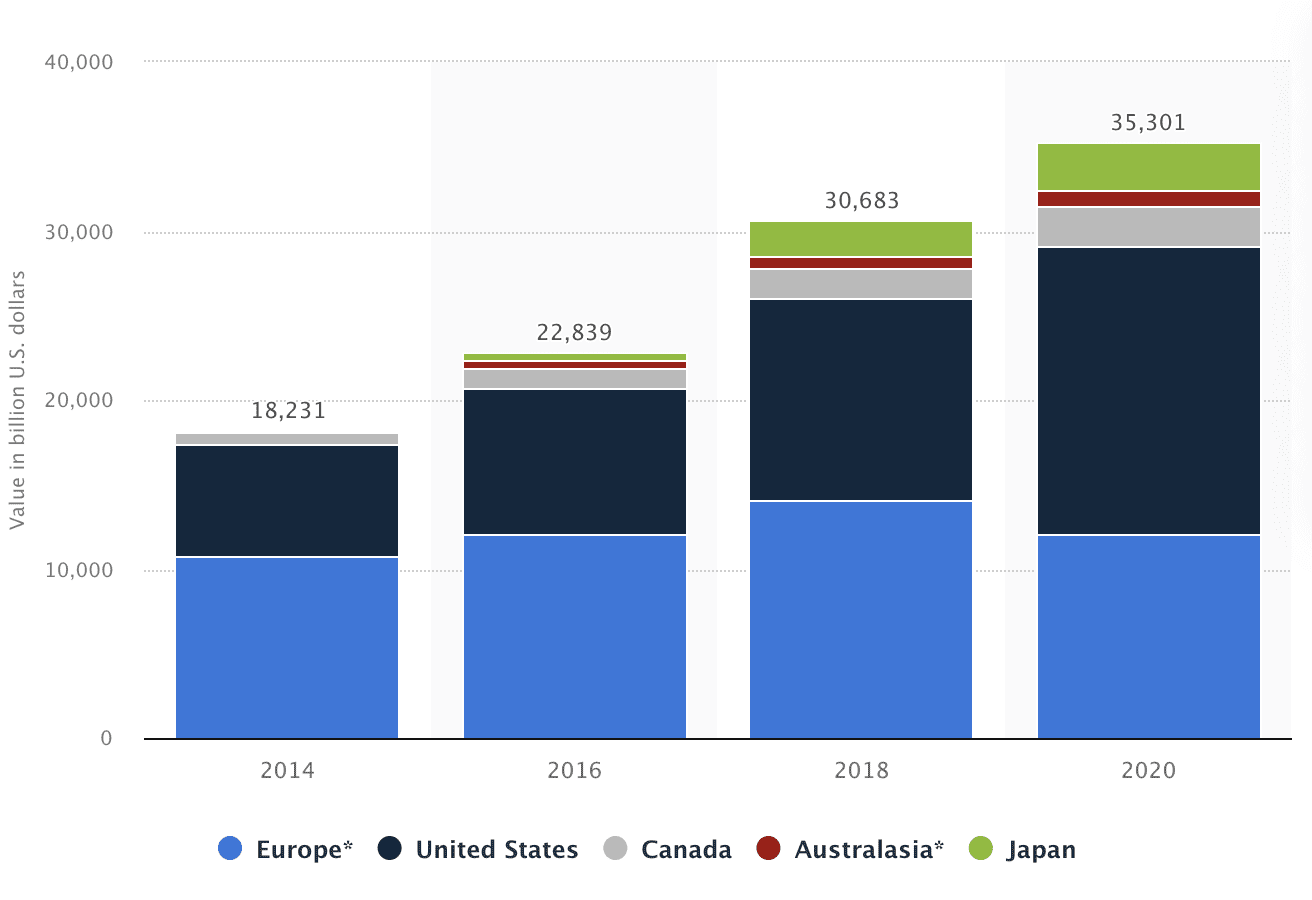

According to Bloomberg, Global ESG assets are predicted to exceed $53 trillion by 2025 if continuing at a 15% annual growth, half the rate of the past five years. In Europe, one of the regions showing the fastest growth, 25% of ESG funds are environmentally focused, while 69% are on the full ESG scope.

This increase of investors looking to “do good” with their money is perhaps a driving force in the popularity of ESG rating disclosure but also may go a long way towards highlighting its potential for doing irreparable environmental damage if not regulated responsibly.

ESGs as a risk mitigator

ESGs were created initially as a tool for risk mitigation. Companies assessed based on how well they perform in the three pillars of ESG can also be evaluated on how well they may act in the future based on changing external factors in these areas.

During the 1960s, socially responsible investment (SRI) was introduced in response to ethical issues and continued to make headway and gain popularity for the rest of the 20th century.

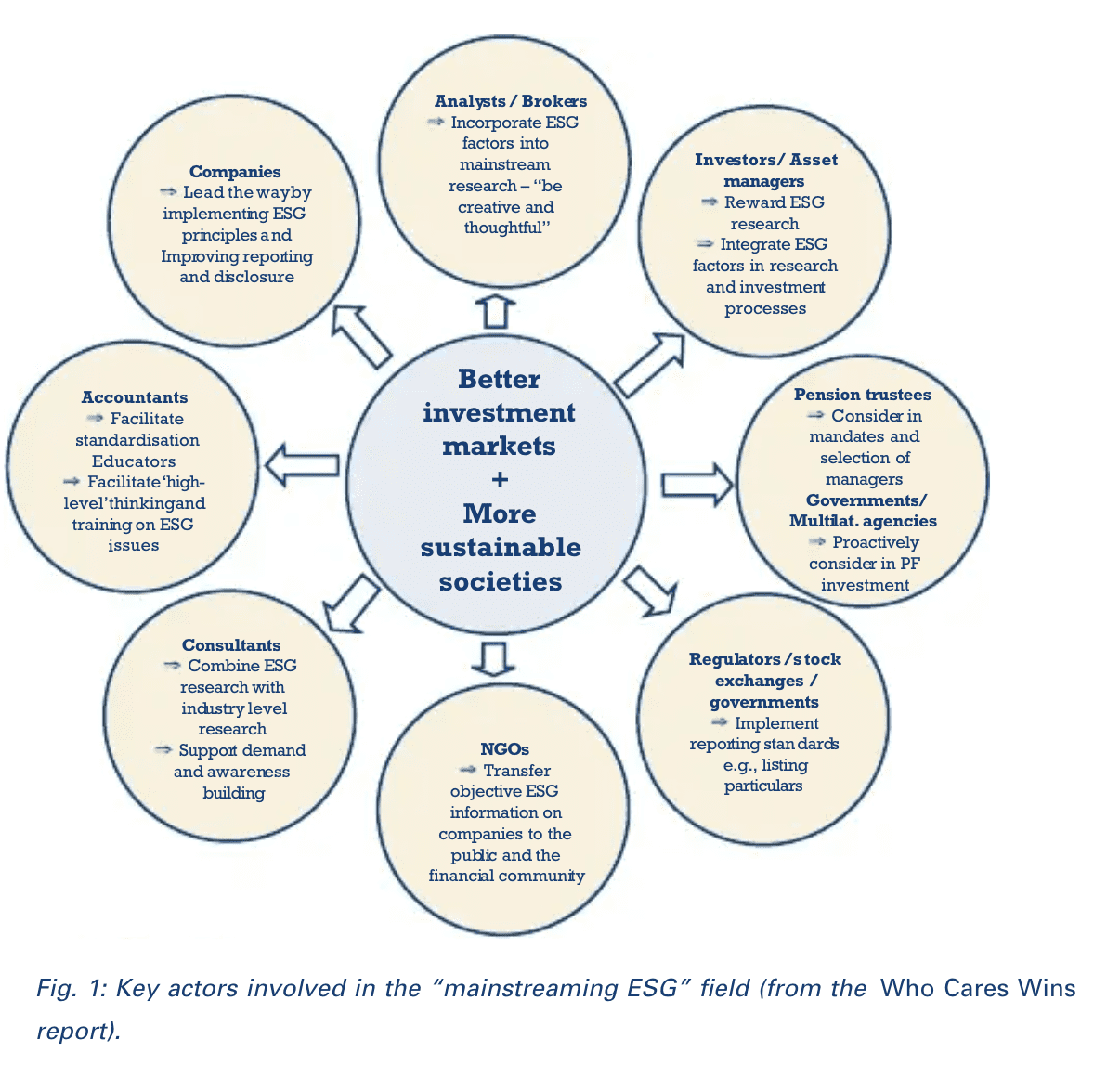

In 2005, ESG was coined in a report following the UN and International Finance Corporation (IFC) “Who Cares Wins” conference.

It was where institutional investors, asset managers, industry consultants and analysts, regulators, and government officials came together to examine the role of ESGs in asset management and economic research.

Within the report, Ambassador Thomas Greminger, then head of the Human Security Division of the Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs, wrote, “The world is smaller, and investing in risky markets such as unstable or conflict-prone regions are not optional anymore but an emerging necessity.”

“As risks to individuals are risks to assets and security of individuals means the security of investments, financial organizations public as well as private, investors as well as governments all share a converging interest in security, stability, and predictability.”

Many of the conference outcomes were focused on long-term investment strategy and how consideration of ESGs adds value to an investment process.

Although mentioned, climate change was mainly in the context of creating “Huge systemic changes in our economies, leading to both risks and considerable opportunities for investors.”

The fundamental point of ESGs was to understand a company’s performance in the three areas and assess its long-term performance for investment gains.

The ‘E’ of ESG

The “Environment” of ESGs has been the sticking point of late. In many reports and articles about ESG investment, the investment strategy is cited as being “sustainable.” A quick google search of sustainable investment will bring up hundreds of articles and web pages referring to sustainable investment and ESGs.

ESGs ratings consider all three pillars, and many companies that do very well in one or two aspects but poorly in others can maintain a high rating.

“ESG was originally thought up as a risk management tool and then hijacked as a tool to attract capital from someone that thinks their making an impact on these issues because it has this label of ESG. That’s not the case; it’s the opposite a lot of the time,” said Duncan Grierson, CEO, and founder of climate impact fintech, Clim8.

“There are trillions of dollars that have been poured into ESG funds as investor money. Investors want to do good with their money. Unfortunately, the data shows that the top 20 funds, the biggest ESG labels globally, hold on average 17 fossil fuel companies in their portfolio.”

Here we see the potential for damage in the misconception of what a high ESG rating means and investment into funds without additional research.

MSCI is the largest global rating agency. Bloomberg reported the company receives 40 cents of every dollar spent on ESG rating worldwide.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and with an increasing focus on climate change objectives, MSCI has had a banner year. The company reported a 54.9% increase in ESG and climate operating revenue in 2021 that was “primarily driven by strong growth from Ratings, Climate and Screening products.”

In a recent survey conducted by Bloomberg of MSCI, it was found that of all the companies studied, the majority of the ESG rating upgrades came from Governance; the Environment only accounted for 26%.

Of these upgrades in environmental factors, many were rated based on the potential impact of the world on the company (climate risk) as opposed to the company’s impact on the earth (climate impact).

In the case of McDonald’s, Bloomberg found that emissions had increased by 7%; however, MSCI gave them an ESG rating upgrade based on their environmental practices. They did this by dropping carbon emissions from consideration due to the conclusion that climate change neither posed risks nor opportunities to the company and by taking into account the implementation of recycling bins, despite their only installation being in locations where regulation deemed it compulsory.

McDonald’s was not the only company to see an upgrade of this kind. Only one of the 155 ESG upgrades was reported from an actual cut in emissions.

Confusion surrounding the ‘sustainable’ terminology

Perhaps the confusion lies in the use of the word “sustainable,” a term that, for many, is synonymous with “climate impact” and, in many cases, is marketed so.

For example, sustainable investment is broken down on a page on the HSBC UK website. It refers to ethical investing, impact investing, and ESG investing under the sustainable investment umbrella.

ESG investing is said to be investing in a fund where the bank “Actively selects companies that meet specific environmental, social and governance requirements. It’s less restrictive than ethical investing as it considers companies adapting, such as oil companies that invest in clean energy.”

While ethical and impact investing are said to avoid fossil fuel companies altogether, positively impacting the climate.

Aside from the subjectivity of the “requirements” referenced, as we have previously interrogated, the issue lies in this seemingly small difference in the companies within the fund receiving the investment.

Many who look to sustainable investment are interested in positively impacting the climate. On average, within the top 20 global ESG funds, each holds investments in 17 fossil fuel firms, six of them in ExxonMobil. For years, fossil fuel companies have avoided significant changes in their practices.

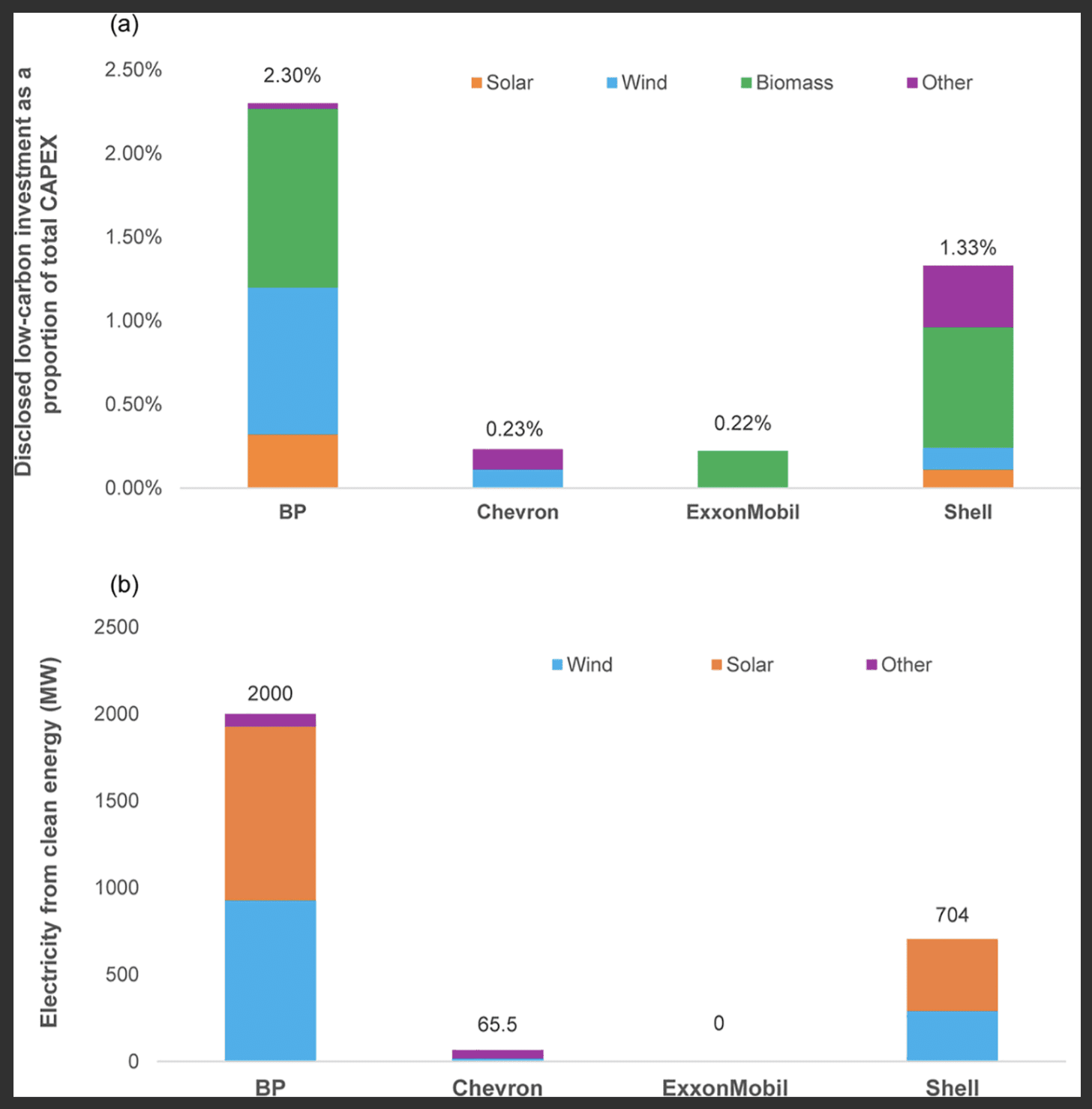

In a journal written by Mei Li, Gregory Trencher, and Jusen Asuka and published in February 2022, it was stated that although discourse surrounding green energy had increased within the publicity of fossil fuel companies, many pledges had been made, little had been done in terms of investment.

The study found that in the four top energy companies, less than 3% of total capital expenditure was on renewable energy. For most, little was translated into actual usage. The investment didn’t result in many impacts.

“An oil or gas company that spends 100 million of capital expenditure, if it spends 2% on renewable energy, that is greenwash, that’s the type of percentage,” said Grierson. “It continues to drill for oil and gas with 98% of its cap-ex, and then the 2% is on the good stuff; it makes a lot of noise about that good stuff in the press.”

As well as fossil fuels, many ESG funds invested in firms in the tobacco and gambling industries raise questions of ethical and social impacts.

Climate risk vs. climate impact

Although ESG investing could theoretically translate to becoming SRI through heightened investor pressure for better company practices, in many cases, it is based on how their practices pose a risk to the company, as we have seen from the MSCI treatment of McDonald’s.

The difference between climate risk and climate impact is at the heart of the ESG issue, and it is here where the lines between SRI, sustainable investment, and ESG blur. The factors, although seemingly related, make up opposite ends of the spectrum.

“They are completely different,” said Grierson. “Climate risk is the risk to your portfolio, wealth, and assets that will be damaged by climate change.”

“An example of this would be an agricultural firm with land in the southern hemisphere, which will be increasingly whacked by climate change. This company will probably be less valuable as it gets more affected by changes over 10 years.”

“Bad management of environmental factors will probably end badly for any company. Therefore, investors may reduce holding in the company or try to influence them to change that.”

“Climate impact is completely different. It’s putting your money into something that will have a positive impact on climate change. Trying to make a difference and trying to turn back time.”

Lack of standardization and regulation

Many cite that one of the main issues with ESG ratings is the lack of standardization. Although standardization and regulation were a significant factor for “mainstreaming ESG” in the 2005 “Who Cares Wins” conference, modern-day rating agencies still vary extensively in their classification.

There are more than 140 different ESG rating agencies around the world. Due to a lack of standardization and regulation, ESGs can portray very different pictures of the companies they are associated with.

“The fact that the rating agencies that we rely on for data vary so much is nonsense,” said Grierson.

“A good example is Tesla. Tesla performs highly on some parts of the ESG and then not so highly on other parts, and that will mean that it will be in each ESG portfolio as a good company or excluded, depending on the rating agency. How can you have such disparate ratings by the agencies? The system is broken.”

Data disclosure

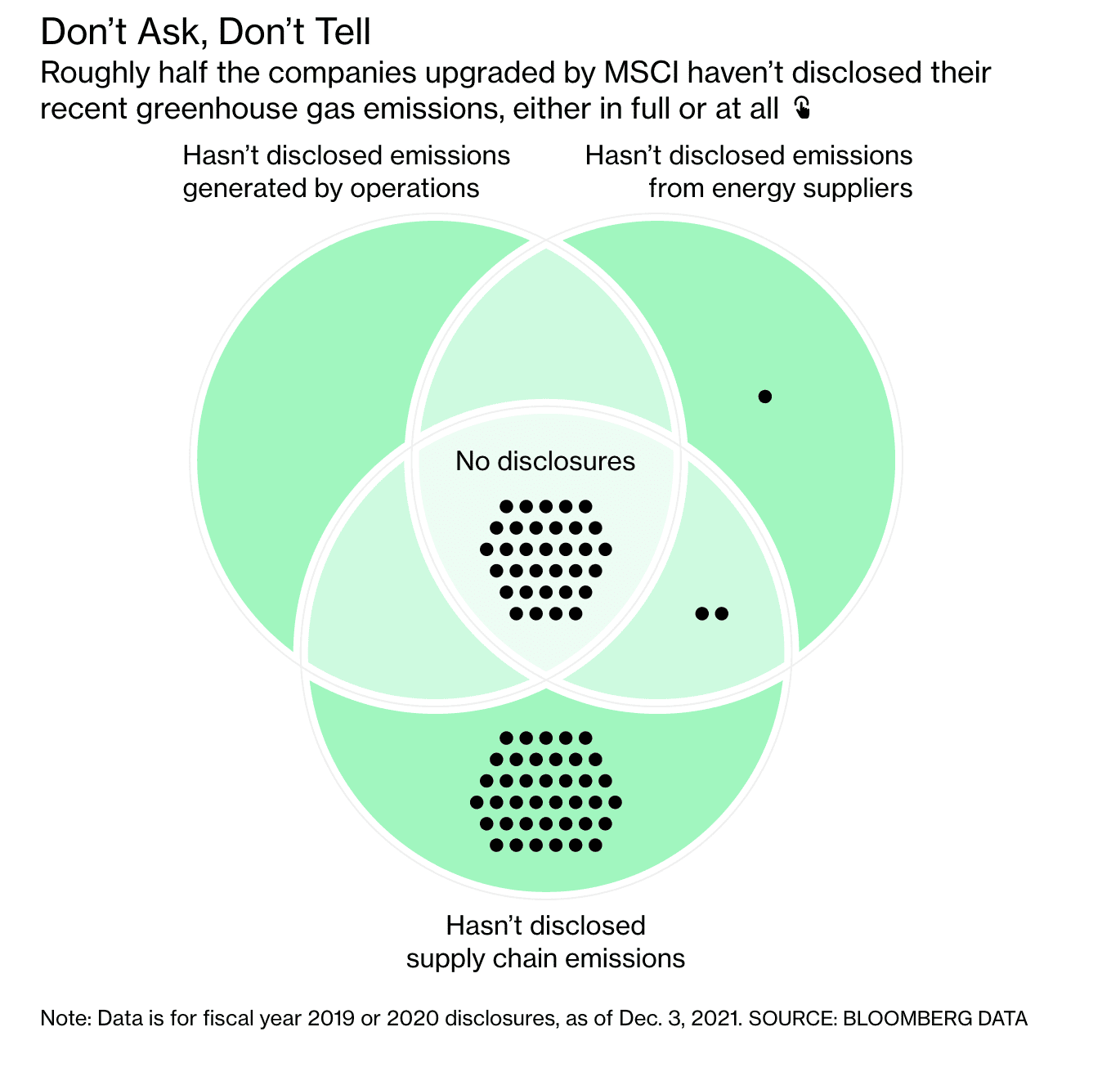

In addition to this, regulation surrounding data disclosure is also vague. Many ESG ratings are based on data companies voluntarily submit. Aside from many claiming a barrier to full data disclosure as confusion and lack of understanding, various loopholes can be used to companies’ advantage.

In the example of carbon emission disclosure, there are three main areas where companies can choose to disclose data; operations, energy suppliers, and supply chain.

In the report on MSCI carried out by Bloomberg, it was found that although many companies did disclose carbon emissions of operations and energy suppliers, they did not include that of their supply chain. However, disclosing any carbon emissions is optional, with many opting out of disclosing any data.

The supply chain carbon emission disclosure issue is not restricted to what was found through the analysis of MSCI.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), supply chain (scope 3) carbon emissions are on average 11.4 times higher than operational emissions, equating to around 92% of an organization’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Emitting this vital information significantly improves carbon emissions data for a company.

Scope 3 emissions are complex to report, especially for international companies with international supply chains. According to MSCI, in 2020, only 18% of constituents said supply chain emissions and even lower percentages were found when individual categories were examined. Despite this, there have been many initiatives to enhance transparency and develop strategies due to the importance of their inclusion.

Regulation initiatives

Awareness of the issues above is increasing, and regulators are starting to take action in response.

In various reports, it has been found that most socially responsible investment is prevalent in Europe and the US. It is then perhaps unsurprising that it is here we are seeing active steps to resolve the issue of regulation surrounding ESGs.

SEC

One of the most significant recent advancements has been that of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). On March 21, 2022, the SEC announced a proposal for rules to enhance and standardize climate-related disclosures for investors.

As well as including disclosures on climate risks on the company and their governance, the rule changes require companies to disclose their operations’ direct and indirect emissions through energy sources and supply chain.

The change would enable and enforce companies to provide additional data, giving further transparency to affect investment decisions.

FCA

The UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has been working towards tackling issues with ESG disclosure for the past few years. In late 2021 they published their “Strategy for positive change: our ESG priorities” report.

In the report, they stated that ESG matters are high on the regulatory agenda, and they would be overseeing the creation of clear standards.

This report built on the strategies outlined by an earlier statement released at the end of 2019, which focused on the themes of transparency and trust within ESG data disclosure.

The report of 2021 built on these two themes by bringing tools, market-led transition, and team strategies and structures to support the integration of ESG into FCA activities focus.

The accompanying Business Plan 21/22 outlined actions they would take, paying particular attention to international coordination by working actively with the IOSCO, the FSB, and the IFRS. An additional focus was regulating the climate-related financial data disclosure, which underpins the ESG ratings, building on the disclosure rules for premium listed issuers implemented in January 2021.

The proposed Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) were first announced in July 2021. They are said to create an “integrated framework for decision-useful disclosures on sustainability across the economy,” bringing together all sustainability-related disclosures under one framework. New rules for disclosure on the levels of corporate entities, asset managers, and investment products are required, to improve transparency within the industry for investors.

Many of the requirements are aimed at large firms. However, it stated that two to three years after the Royal Assent of primary legislation, the requirements would be opened to all companies, asset managers, and investment products.

In addition to this, the UK Green Taxonomy was created to set out standardized criteria for specific economic activities to be determined appropriately as environmentally sustainable.

Although standardized and assessed by the government, the Taxonomy has two areas that currently align with ESGs. The first is that they are based on reported disclosure, where the SDR becomes significant in addressing this. The second considers the transitional aspect that many companies may not have the technological capacity to reduce emissions. For some activities, changing the threshold from taxonomy alignment to best-in-sector potentially causes misconceptions on whether an action is environmentally sustainable.

Both approaches are referenced as following the European Union model for regulation.

The EU model

According to the International Regulatory Strategy Group, “The EU Taxonomy provides the most comprehensive framework developed to date to identify economic activities, sectors, and companies that are contributing to meeting the Paris Agreement’s goals and advancing environmental sustainability more generally.”

For many regulatory bodies, it is the model they base their regulation on, as we have seen in the example of the UK.

The EU Taxonomy Regulation entered into force on July 12, 2020, establishing six environmental objectives. These formed the basis of the EU Taxonomy, which, like the UK Taxonomy, is a classification system used to rate companies based on their environmental impact to create a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities.

In February 2022, an additional act was presented to accelerate decarbonization, introducing specific disclosure requirements for businesses related to their activity in the gas and nuclear energy sectors. This extension aimed to accelerate a shift from fossil fuels to a carbon-neutral status.

As well as taxonomy, the European Commission adopted a directive on corporate sustainability due diligence on Feb. 23, 2022. They identified the need to encourage sustainable and responsible corporate activities by implementing new rules, ensuring companies address the adverse impacts of their actions.

This significant proposal targets all areas of ESG, ensuring compliance throughout the operations of companies, their subsidiaries, and their supply chains.

Although currently targeting large corporates of 500+ employees worldwide, large companies in high-impact sectors such as textile production and Non-EU companies of similar size generate turnover within the EU, they predict that SMEs could be indirectly affected by supporting measures.

It marks the first step towards active regulatory engagement in ensuring compliance with responsible behavior standards.