There is much debate surrounding the introduction of digital currencies into the mainstream financial system.

Many are concerned about environmental factors and dystopian scenarios of extreme government surveillance and worries about financial exclusion.

To quote Dan Held, ex-Director of Growth Marketing at Kraken, Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are “not bitcoin” in more ways than one.

CBDCs aren’t cryptocurrency

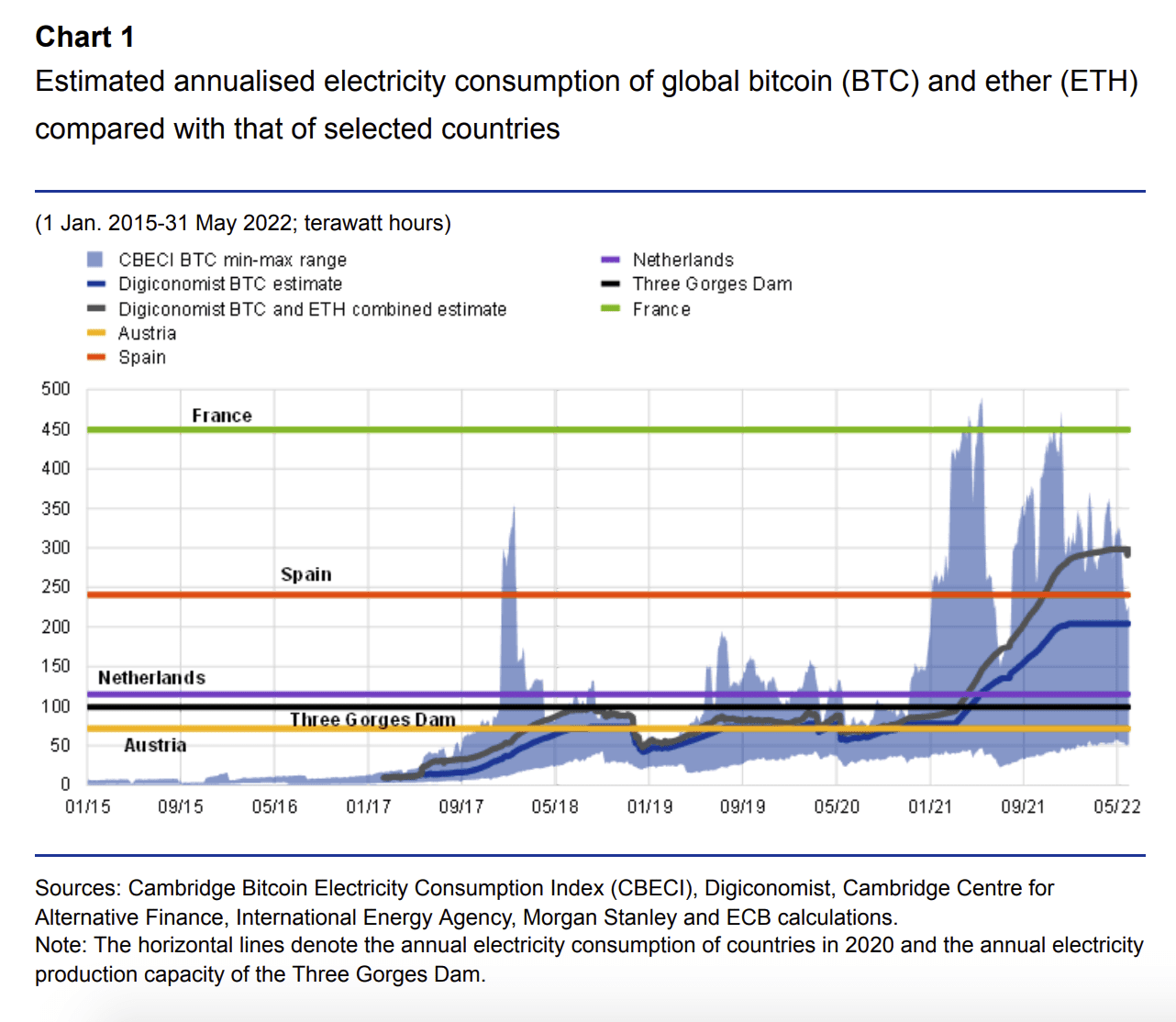

Bitcoin is notorious for its energy usage. Since its birth, the Proof of Work (PoW) consensus system underlies the asset and has been criticized for its energy consumption. In a recent report released by the International Monetary Fund, it was found that the annual electricity consumption of the bitcoin network is estimated at 144 terawatt hours (TWh) per year. This amounts to about 0.6 percent of total global electricity consumption, equivalent to the energy consumption of Austria and Finland combined.

In addition, the e-waste of the network (referring to the electronics discarded at the end of their useful life) is equivalent to that of a small country such as the Netherlands.

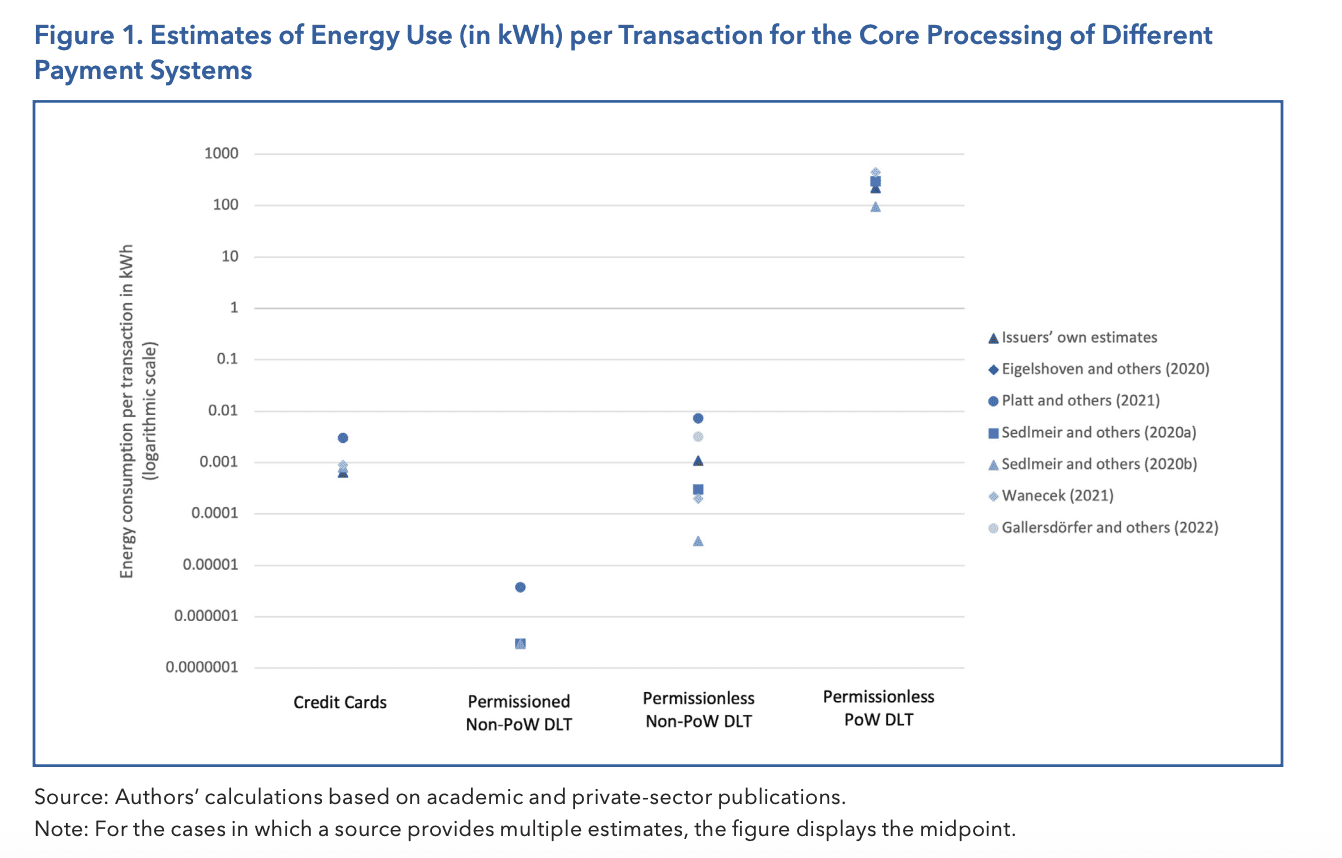

PoW was inherited by many of the early cryptocurrencies, although other consensus mechanisms have since been developed. These alternative permissionless systems reduce the environmental impact significantly, almost to the point of Credit Card usage.

CBDCs are not, however, designed to use any of these mechanisms.

“The general public harbors a major misconception about CBDCs and conflates their energy use with bitcoin or crypto,” said Richard Turrin, author of Cashless: China’s Digital Currency Revolution. “This is very common, and one of the more common comments I receive is a concern about the energy use of CBDCs.”

New research shows they could be the most environmentally sustainable way to handle the monetary system.

Back to basics: The environmental impact of cash and card

“The energy used in the lifecycle of paper banknotes is highly variable because it supports entire industries surrounding printing, minting, transporting, handling, and storing cash,” said Turrin.

“Figures from Cashless show the enormity of these costs which have energy use embedded in them: The US Treasury’s budget for printing cash alone was an astounding $877million.”

De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), the central bank of the Netherlands, evaluated the environmental impact of debit card payments.

According to the World Bank, the DNB found that the total ecological cash effect was 1.5 times that of card payments. Ripple came to a similar conclusion, finding card payments to have less of an impact than both cash and blockchain assets such as ethereum and bitcoin.

Per transaction, the estimated energy consumption of card payments is significantly lower than other forms of payment, ranging between 0.0006KWh and 0.0008KWh, depending on the provider. Cash is around 0.044KWh, while blockchain assets reside in the hundreds.

Ripple’s report stated, “The environmental cost of paper money has far greater scope beyond electricity consumption. Paper production, printing, and waste disposal contribute to eutrophication, global warming, photochemical ozone creation, and human toxicity. The transportation of paper money leads to greenhouse gas emissions. Physical banks and chest branches that serve as paper money vaults also consume significant electricity from computers, lights, heating, and cooling.”

It seems that centralized digital payments such as card payments are significantly better aligned with environmental targets of the existing payment methods.

Available technologies and devices such as smartphones could be harnessed to reduce digital payments’ impact further.

In the case of CBDCs, the IMF suggests digital wallets stored on users’ smartphones, without the need for additional devices, could reduce reliance on card payment networks. However, offline solutions may still require physical cards.

Permissioned vs. permissionless

As central banks develop their systems towards a more digital focus, they turn to real-time gross settlement (RTGS) systems to handle the settlement, opening them out to CBDC potential. RTGS would speed up settlement times, so they happen almost instantaneously, as opposed to the periodic system of yesteryear, processing every few days within standard working hours of the presiding jurisdiction. The RTGS system could issue CBDCs to help manage accounts, balances, and settlement processes.

The RTGS system revolution is relevant because with it comes the use opportunity for Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and blockchain, bringing CBDCs into a similar infrastructure to cryptocurrencies.

According to the IMF, most current CBDC projects are based on non-PoW permissioned DLT or modernized versions of traditional payment architectures such as TIPS.

Experts suggest that DLT and blockchain could be used to replace the database within RTGS, providing a decentralized alternative that could make security more robust. CBDCs would then be a hybrid solution combining the centralized RTGS with decentralized DLT.

One of the main underlying factors in their environmental advantage seems to hang on to the permissioned nature of the proposed DLT underlying this CBDC design. Unlike cryptocurrencies that work within a trustless, permissionless ecosystem, CBDCs would be used with a centralized entity and users that have verified their identities to gain access.

“The big difference with DLT is whether it’s permissioned or permissionless,” said Turrin. “So if it’s a permissionless, public DLT, it uses more electricity than a permissioned DLT, where you know who’s using it. Therefore, you have lower levels of security.”

“Crypto is designed to be fully public and trustless, which requires bullet-proof systems that are notorious for energy consumption,” continued Turrin. “Even with more advanced “proof-of-stake” consensus replacing “proof-of-work,” crypto will still use more electricity in part because of the job it does.”

Central bank focus critical to environmental impact

Regardless of whether a CBDC uses DLT, the IMF argues that CBDCs could improve the environmental optimization of monetary systems. The secret lies in its design.

The inclusion of new technology such as permissioned DLT, cloud services, or smartphone interoperability could be assessed for inclusion based on their environmental inclusion.

CBDCs are still in their infancy. The idea and design are still under construction within many different projects and jurisdictions, so there could be a scope to set these parameters early on. Many new technologies are being developed which could be positioned to improve the environmental impacts of traditional finance. As compliance and reporting standards become more regulated, their potential is enhanced.