The Trump Administration has telegraphed significant changes to GSE mortgage lenders — with massive implications for the industry

Since his swearing in on March 14 as the fifth Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), construction mogul William J. Pulte has executed major policy and personnel changes. Among other moves, Pulte has named himself board chair of the Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, removed 14 of the GSEs’ 25 sitting board members, fired most of the companies’ audit boards, generally slashed headcount, and rescinded several Biden-era oversight-related advisory bulletins.

According to Professor David Reiss of Cornell Law School, a scholar of real estate finance and housing policy, Pulte’s simultaneous leadership of the FHFA in addition to roles at the GSEs, which have been under federal conservatorship since the 2008 financial crisis, is not normal.

“The whole point of regulation is you have somebody who’s overseeing an industry,” he told Fintech Nexus. “This is like the left hand [knowing] what the right hand is doing: You’re overseeing yourself, so it’s … kind of inconsistent with the notion of a supervisory regulator.”

Fintech Nexus contacted the FHFA, requesting that it comment on the impetus behind Pulte’s simultaneous self-appointments to Fannie and Freddie. The FHFA did not respond.

AN END TO CONSERVATORSHIP?

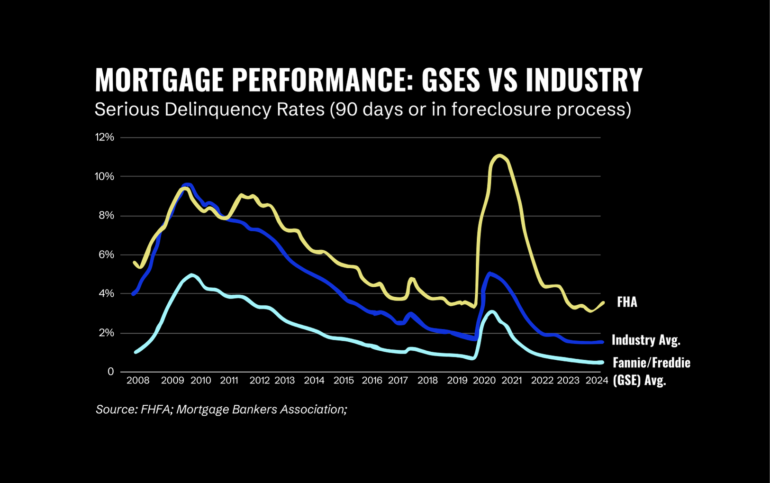

Statements from Trump Administration officials suggest a commitment to re-privatize Fannie and Freddie and end their conservatorships despite their current risk-averse performance, which includes serious delinquency rates three times lower than the industry standard. Considering Fannie and Freddie back 70% of the US mortgage market, removing federal guarantees assuring the GSEs’ risk could raise prices; doing away with other forms of public oversight would likely leave non-traditional borrowers as well as a range of financial institutions at a major disadvantage.

A statement from the Mortgage Bankers Association suggests that ending conservatorship carries significant risks that even its boosters see as possessing “playing-with-fire” attributes.

We support efforts toward the GSEs’ release, but it must be done transparently, with an ample timeline that includes stakeholder feedback, and most importantly, it must include an explicit federal backstop of the GSEs’ mortgage-backed securities. Any move must protect both consumers and the housing finance system from market disruption.

Sara Levy-Lambert, Head of Operations at San Francisco-based real-estate investment platform Awning, said the removal of government guarantees could result in “more market volatility, increased pricing of financing options, and reduced investor confidence.”

In the event that government backstops were entirely removed — a drastic shift that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has seemingly shot down, claiming that any GSE release would be tied to mortgage rates — Levy-Lambert said she anticipated Awning to secure more strategic partnerships with non-GSE-backed lenders to ensure access to alternative funding sources.

“We could also explore a more robust transition toward tools enabling data-driven, real-time analyses of the market to assist both the investor and consumer in making more informed choices in a volatile market,” she told Fintech Nexus. “This can be an enhancement of our technology platform to provide clients greater clarity into the changing mortgage rates, credit risk, and other related metrics … Opportunities for innovation, but with challenges to liquidity and affordability, are on the horizon with a move away from a GSE-backed environment towards one that relies more heavily on private players.”

FINANCIAL SECTOR RIPPLE EFFECTS

Other institutions affected by the fates of Fannie and Freddie have even fewer paths of recourse. According to Carrie Hunt, Chief Advocacy Officer of industry group America’s Credit Unions, better access to the secondary mortgage market, fairer pricing models, and government guarantees to reduce risks have benefited credit unions and their more than 140 million members.

Returning to an unimpeded private-market model wherein high-volume providers of mortgages receive preferential rates would favor large financial institutions over smaller players — with negative effects for smaller mortgage-originating fintechs. As Fitch noted in March 2024, the US mortgage market has consolidated around non-bank mortgage lenders, which are “aided by scalable technology platforms, diversification from servicing cash flows, relatively low corporate leverage and access to liquidity that affords them the flexibility to withstand market cycles.” Major exits, parings-back, and collapses within the space — Fairway, Citizens Bank (NYSE: CFG), loanDepot (NYSE: LDI), HomePoint, and Wells Fargo (NYSE: WFC), among others — mean remaining large players can increase their share of the pie, including through acquisitions, like Rocket Companies’ (NYSE: RKT) recent acquisition of Mr. Cooper (NSDQ: COOP). Privatizing GSEs without protecting the unit economics of smaller institutions would only exacerbate existing market dynamics and accelerate consolidation.

“As discussions on housing finance reform and the GSEs’ future under the Trump Administration develop, we will advocate for efficiencies and protections for credit unions and their members in need of these loan options,” Hunt said in a statement.

CAPITAL IDEAS

One idea percolating is for the Trump Administration to use Fannie and Freddie as a pool of capital to inject into a sovereign wealth fund. An op-ed in the Financial Times by Stifel CEO Ronald Kruszewski suggested this reconfiguration could provide “continued government backing,” “stabilize investor confidence,” and “pave the way for a $1 trillion sovereign wealth fund by 2040.”

However, in a letter to the editor in the Financial Times, Dini Ajmani, Former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the US Treasury, suggested the idea would fail, as any privatization of the GSEs would require proper capitalization, taxpayer compensation, and adequate confidence of securities investors.

“I believe the difficulty in meeting all three conditions is why [the] status quo has persisted,” Ajmani told Fintech Nexus. “To build capital, Fannie/Freddie must retain earnings, which means the taxpayer is not compensated. If the taxpayer is compensated through dividend payments, private capital will be uninterested because the agencies will be undercapitalized.”

To this end, FHFA Director Pulte may continue to atrophy many forms of GSE oversight as a way to prime the pump: Pre-empting congressional activity by deregulating Fannie and Freddie can accelerate their transition toward open-market frameworks.

The Trump Administration may see it as its only viable short-term avenue, as many members of Congress are uninterested in bringing Fannie and Freddie out of conservatorship; Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), member of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, called the move “Great for billionaires, terrible for hardworking people.”

Should the Trump Administration succeed in its quest, we may see states attempting to fill in the gaps on regulatory accountability, rhyming with blue-state attorneys-general’s litigiousness in the wake of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s de-clawing, though this is unlikely.

“State regulators do not generally play a role similar to the two companies (except to some small extent state Housing Finance Agencies),” Reiss of Cornell Law School said. “I could imagine state agencies trying to increase consumer protection for mortgage borrowers, if the federal regulatory environment changes, but we would have to see how that plays out to understand how the states would respond.”