Ever since the retail trading stock blow-up of Gamestop and AMC early this year, Robinhood and feeless stock trading have been the talk of the town.

The system Robinhood and other brokerages use, Payment for Order Flow, which enables free trading has brought in millions of new investors and billions for brokerages.

But some critics warn the practice also breeds conflict of interest that leave customers worse off than before.

Last week, Robinhood and partner firm Citadel Securities were back in the news for PFOF over a new class-action: Looking at its past, is the practice the future of investing, or a barely legal kickback?

Who started this gig?

With the rise of feeless retail trading options since 2018, PFOF is back in the news, but it’s not a new thing. PFOF has been a contentious issue for more than 30 years: there were brokers using the practice even back in the 80s.

Going back to find the source of PFOF is to look deep into the history of Wall Street.

It all begins with, like many things, government intervention and a con man who found a way to print money.

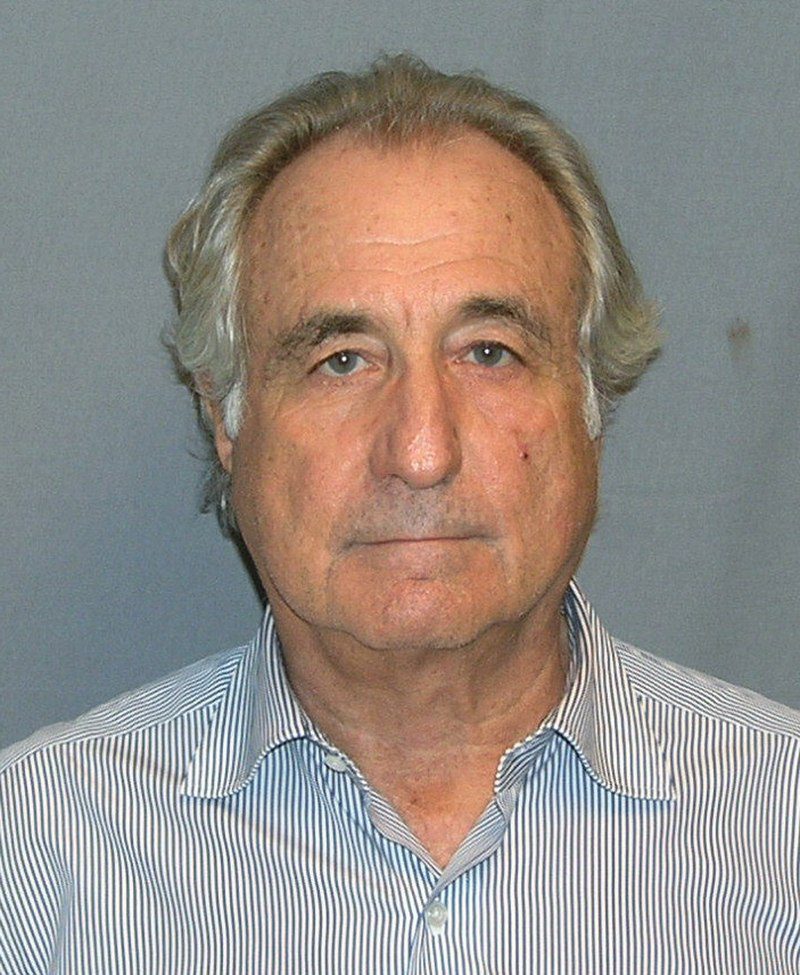

In a win for the naysayers, Bernie Madoff is credited as the earliest proponent of the scheme.

Before being discovered as the creator of a $64.8 billion asset management Ponzi scheme, Madoff was a top market-maker on Wall Street, an innovator of electronic trading systems.

In the ’60s, right out of college, Madoff began as a pink slip “over the counter” penny stock seller, trading stocks in a secondary off-market pool from the NYSE.

In the 20 years that followed, Madoff’s traders rose to become the top market makers in the country, absorbing up to 10 percent of the NYSE volume by 1990.

Electronic trading, through the innovation of decimal fractional trading and PFOF, helped Madoff reach the top. Madoff also championed a practice that had begun in the ’80s: paying bounties for the first look at orders.

Government intervention… yay

In 1975, Congress directed the SEC to “amend any restrictions which imposed an unnecessary, inappropriate burden on competition.”

By 1983, the SEC complied, requiring trading data to be broadcast accessibly to the public.

Once proprietary to floor traders in Wall Street, live stock prices were suddenly available to competitors, retail traders, and firms like Bernard Madoff Investment Securities.

Using the new data, Madoff and others competed by transferring the fees traders would normally pay on the NYSE to brokers: Madoff’s marketers would pay brokers pennies per stock trade sent to them. Madoff’s system would then connect trades and split the difference between the bid-ask spread. They were paying for orders to flow their way.

For example, today the same system would connect someone selling Gamestop for $50, and someone buying GME for $50.01. Madoff sells it for $50.01, but gives the seller just $50, taking $.01. That cent is then split between paying the exchange that sent in the trade, paying Madoff, and ensures the retail customer had free trade or price improvement.

Seems like, well, pennies on the dollar, who cares? But multiplied by 100 shares, that’s $.50 for the market maker, $.50 for the exchange. What about by a million? Or a billion? Madoff and his contemporaries made hundreds of millions. Then, the legal limit for fractional shares dropped from an eighth of a dollar to a sixteenth in 1997, down to decimals in 2001, and the practice became less common. It was at this time that some believe Madoff looked for other ways to make money.

As he told a CNN finance interviewer in 2002, PFOF was down to fractions of cents payments to get orders from exchanges, and it would only go lower from there. But he still defended the marketing scheme.

“No one tells a firm how they can advertise. If I want to hire salesmen to generate order flow, no one is going to object. I don’t have them. So if I want to use Fidelity’s salesmen and pay part of my trading profits in the form of a rebate, why shouldn’t I be allowed to do it? It was characterized as this bribe and kickback and something sinister, which was very easy to do. But if your girlfriend goes to buy stockings at a supermarket, the racks that display those stockings are usually paid for by the company that manufactured the stockings. Order flow is an issue that attracted a lot of attention but is grossly overrated.”

SEC perks up

The attention came in the form of the SEC. Though never finding a way to outlaw PFOF, regulators were still worried that paying for orders could make the end consumer worse off.

In 1984, the SEC had petitioned the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) to investigate PFOF and look for problems. The NASD is a self-regulatory body outside of the government, now called FINRA.

After years of research, in 1990, NASD came back with an answer: The report found no legal basis for restricting the practice of payment for order flow.

Still, it recommended that the NASD members should be required to disclose in advance the “factors that influence their order-routing and execution decisions.”

Madoff was chairman of the board of directors and a member of the board of governors of the NASD, which ran the Nasdaq exchange.

The trading scheme was making millions, and in the end, price improvement on the face of the transaction was enough. By offering PFOF, Madoff brought in enough volume to outsize the competition and absorbed a large fraction into a secondary market using his electronic trading systems.

Most of the world was still stuck trading through brokers working on the floor of the stock exchange, and Madoff was leading the charge for computerized trading systems. The “Primex” software he bought would eventually become the basis for the Nasdaq system.

Madoff outright helped develop the Nasdaq electronic trading system, according to “What Goes Up: The Uncensored History of Modern Wall Street.”

“We were involved in the design of the Nasdaq technology. It wasn’t genius, believe me. A lot of people give us credit for being these brilliant technologists, the technology was very basic.”

While that tech would become the second-largest exchange globally, it began as a collection of self-regulating “dark pools” of capital.

Though market makers have a fiduciary and legal responsibility to offer the best prices to clients, the act of fulfilling orders by paying for them in an off-site pool still freaks out critics.

After the 90s, Madoff would go on to rake in billions toward a shadowy asset management branch of his firm.

The story goes that two brokers would use a specialized computer program to fake print backdated sales reports on client account earnings. After his sons turned him in, he lost everything and recently died in prison.

In the days and years following Madoff’s arrest and trial, reporters began to look more closely at the practices of his electronic trading and PFOF — now that he was proven to be a giant fraud.

Here and now

The worst of the allegations direct the blame at liquidity providers like Madoff and modern-day brokerages like Robinhood for targeting uninformed traders to make the biggest bang of their buck.

For PFOF, the product is not offering free and attractive retail investing but instead selling retail investor trades to market makers in dark pools of money.

These are the worrying pools of cash outside of exchanges SEC chairman Gary Gensler warned about in a recent Senate hearing, saying, “I think it may make our markets less efficient; retail traders may not be getting the best execution even if with a price improvement [feeless trading].”

“If anyone on this Commission or this staff makes a trade on these platforms, it is 97 percent chance that it does not go to an exchange; it goes to dark markets and secondary sale.”

Gensler believes Citadel has marketed itself as the executor of half of all retail volume. His insinuation that most retail investing occurs off exchanges has been a worry for 20 years.

Rob Curren, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, talked with hedge funds in 2008 and found that little was stopping them even back then from misreporting their interior markets.

One portfolio chief for TFS Capital told him the only thing stopping him from gouging clients of dark pools is his lawyer and his scruples.

‘Free money’

“It’s free money,” said Richard Gates, money manager TFS Capital. “It’s a neat inefficiency in the marketplace, and dark pools are growing tremendously in size.”

Back then, the share of investing that occurred off exchanges was 8.5 percent. This past year, trader Aenea Sandvig found that off-exchange trades made up 40 percent of all volume.

Today, Robinhood markets itself as a democratizer of investing. CEO Vlad Tenev took to the WSJ last Monday to opine and defend his firm’s actions.

Concurrently, Citadel Securities, the market maker that enabled meme stock retail trading, took to Twitter to deny new allegations in a lawsuit.

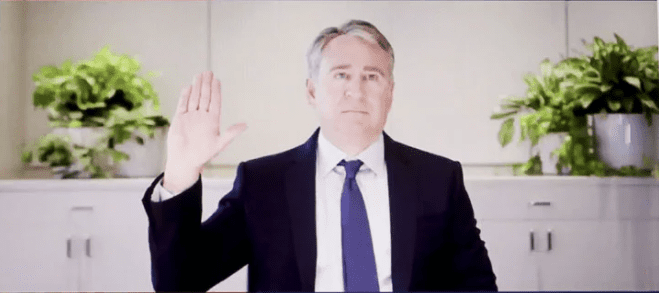

Robinhood and Citadel’s Ken Griffin have denied under oath that any meeting took place, but new leaked communications from Robinhood at least allege a meeting was planned to discuss the stock trading frenzy.

The lawsuit, a class action filed in Florida, alleges that the firm talked with Robinhood back in January, and shortly afterward, trading was halted for meme stocks on the exchange.

It’s not the first time Robinhood has faced legal action over PFOF: In December of last year, Robinhood agreed to pay the SEC $65 million for failing to disclose the receipt of payments from the firms it sold orders to — not admitting any fault.

The U.S. is one of the only western countries to allow PFOF; Canada and the UK have both banned the practice.

Again, it is not that retail investment platforms sell trades to market makers for profit — as Thomas Peterffy, Chairman of the Connecticut-based Interactive Brokers told Reuters.

“The better the execution price, the less money the market maker earns,” Peterffy said.

“But this has been the story forever on Wall Street. This is how the large investment banks make about $250 billion per year. They call it ‘trading profits.'”