Researchers from the University of Texas published a study Tuesday morning that claims fintech lenders who participated in the Paycheck Protection Program dropped the ball on underwriting. However, by the study’s own admission, the lenders were required only to believe applicants’ claims and get the money out of the door.

The study flagged $76 billion in PPP as suspect to misreported application data. $21 billion of those loans came from fintech lenders. Cross River Bank, a well-known tech partner community bank, was explicitly named as a top offender, but researchers never actually saw lending data. Instead, as the lenders will attest, the claims are fabricated guesses.

Phil Goldfeder, head of public affairs at Cross River, said that the study paints a portrait the opposite of reality. PPP aimed to help SMBs, but many traditional institutions serviced only existing clients or even just a subset, leaving those hardest hit by the pandemic (small business owners without good bank relationships) in the dust until fintech stepped in to help.

“Unlike other lenders who prioritized their own customers, Cross River addressed the SBA call to action and did not limit the program to existing customers,” Goldfeder said. “As a result, it was able to reach almost half a million of the smallest and most vulnerable businesses in need.”

The study itself seems to agree, citing Erel and Liebersohn Does fintech substitute for banks? Evidence from the Paycheck Protection Program supports that “FinTech lenders increased access to the PPP by lending more in zip codes with fewer traditional banks, lower incomes, and higher minority percentages,” the study said.

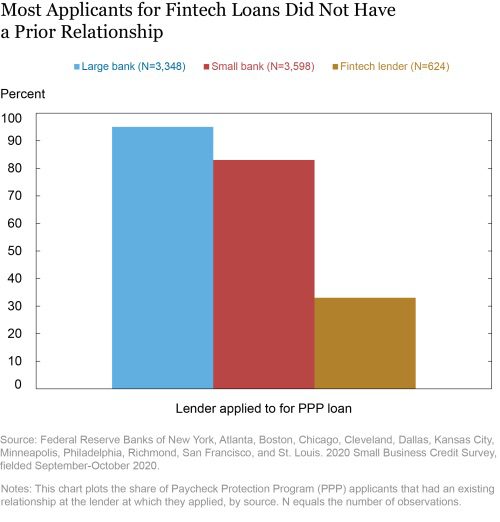

A credit survey from October 2020 supports these findings, showing the results from the Federal Reserve banks of major cities, including New York, Chicago, Boston, and Cleveland. For example, the Fed published that one in four black-owned businesses used fintech lenders to apply for PPP. In addition, the Fed also found among large banks, over 90% of PPP lending was to previous clients, compared to just 30% of PPP lending from fintechs.

How did the 95-page study miss the mark? Students Samuel Kruger, Prateek Mahajan, and Professor John M. Griffin created nine traits to examine the possibility of misrepresented PPP loans. Their work was published Tuesday morning and quickly translated into news. By Tuesday afternoon, the study has spawned headlines like Bloomberg’s “Fintechs Found to Be Much More Likely to OK Suspicious PPP Loans.”

But the measures are not actual fraudulent loan data, just indicators of problems with how borrowers reported information on a loan form. For example, the four most essential indicators checked if a recipient business was registered, if there were multiple loans at the same address, whether the business seemed to receive too much money “based on industry norms,” and whether the PPP data conflicted with EIDL program.

If these “indicators” showed up alongside the five secondary traits, such as whether a borrower had a criminal record, then the study argued the borrower misrepresented. Another secondary trait was similar loans under the same lender in the same county.

The study itself admits that “PPP lenders were required to follow SBA lending guidelines but did not bear any credit risk themselves. While the lenders were required to collect documentation from loan applicants and to follow Bank Secrecy Act requirements, they were explicitly allowed to rely on borrower certifications and representations and do not face liability for borrower misstatements.”

The SBA did not provide strict guidelines for applications. The rules were created in April 2020, when the country felt like the early stages of an apocalypse movie. Even if the year-long regulation was a rush order, and the SBA’s guidelines were lax, fintechs and traditional lenders alike had set in place in-house underwriting safeguards, and the report’s researchers never laid eyes on them.

“Cross River stepped up to answer the mandate from Congress and, in the process, deployed fraud detection standards that far exceeded the continuously evolving SBA program requirements,” Goldfeder said in a statement.

In March 2021, the House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis looked into the mismanagement of PPP, hearing testimony from SBA Inspector General Hannibal Ware. Ware found evidence for fraud, some egregious cases involving stolen millions and freshly purchased Lamborghini’s, but could only find $3.6 billion of potentially bad loans in the program.

“Due to complaints of fraud received by the OIG, we collaborated with the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) Do Not Pay (DNP) Business Center, which identified high-risk transactions related to financial assistance to small businesses for the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ware said in testimony. “Our review of Treasury’s analysis showed approximately $3.6 billion in PPP loans to potentially ineligible recipients.”

Just last week, a group of bipartisan Senators praised the help of fintech lenders in the PPP. Sen. Tim Scott, R-SC, and John Hickenlooper, D-CO, introduced legislation to allow fintech lenders in the SBA’s 7(a) loan program.

Two of the fintechs named in the study with a high amount of suspect loans have sent letters to the president of the University of Texas. One from Capital Plus CEO Eric Donnelly finds the data used in the study wholly wrong and known to the industry as outdated.

“Professor Griffin claims to have reviewed all loans produced by Capital Plus for the time covered, however, given the limitations of the SBA’s published data, he has no way to know which of the loans reported were actually funded,” Donnelly said in the letter. “The data includes loans that Capital Plus never in fact made, and the number of these over-reported loans is staggering.”

Another letter from an attorney representing PPP lender BlueAcorn LLC said that even if the study used updated data, their in-house fraud detection denied many that the SBA had already let through.

“There is additional data even beyond the June 30 data that greatly impacts any analysis. But more importantly, it does not take into consideration the large number of applications that we received and denied, even after SBA approval,” Lawyer Jonathon Frotkin said in the letter. “Of course, without knowing the numerator, it is impossible to conduct a rigorous analysis.”

He also wrote that it was just “bad poker” to tease out the study under news embargo to USA Today and media companies before even asking for the input of the financial companies that were involved in the first place.

Goldfeder from Cross River said that fintechs as a whole were trying to help where traditional banks would not, and they are being thrown under the bus for it.

“Small businesses are still working to recover from the devastating impact of Covid,” Goldfeder said. “And it’s disappointing that some would use misdirected criticism, gross assumptions, and unsubstantiated claims to undermine the sacrifice and countless hours that were dedicated to getting the American economy back up and running.”