In November of 2015, Rob Law and I founded DailyPay in my basement. On a second hand whiteboard propped up against a wall, Rob, Andrew Yoo (Developer 1), my dog Jack, and I derived the key formulas we needed in order to move money before payday, and importantly, the code for how to get paid back. We began with a simple problem to solve – workers need access to the pay they’ve earned before payday because it’s their money. Every single business decision, product decision, engineering decision, marketing decision, and regulatory decision we ever made found its North Star in this foundational principle: It’s your money and you should have complete control over it.

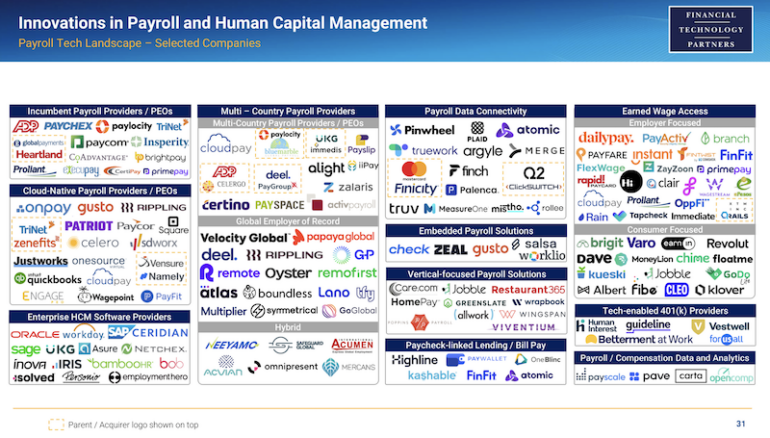

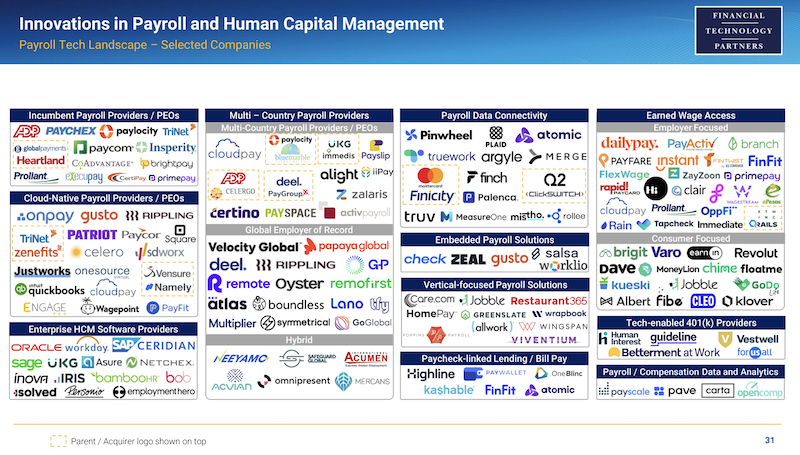

Eight years later, on demand pay and earned wage access is its own industry. According to FT Partners, there are 35 companies in the United States offering on demand pay as a standalone offering. It’s now become its own category within financial technology and human capital management.

Source: FT Partners

On-demand pay has been adopted by major payroll companies and HCM providers like ADP and Ceridian. By count, 10 out of the top 10 HCM companies have some type of offering and/or partnership with one of the solution providers. It has even extended to major financial institutions such as JPMorgan, Citizens Bank, PNC, U.S. Bank, and others, who have recognized the significance of on-demand pay and have incorporated it into their suite of offerings. A few months ago, I collaborated with Professor Marshall Lux of Harvard University on the state of the on-demand pay market. The team at Harvard concluded that 4 out of 10 low income workers now have access to some type of on-demand pay provider. Truly astounding.

Today, I believe the on-demand pay industry is at a critical inflection point. On one hand, before the holidays, I was having coffee with the President of a Fortune 100 company who began offering on-demand pay two years ago. He glibly observed “On-demand pay is table stakes at this point. Every employer is offering it.” At the same time, regulators and lawmakers have begun to articulate positions that offering on-demand pay is a form of unlicensed lending activity, which if codified, would impede the growth of a critical service for low income workers.

We are in an important moment right now. It’s a moment to pause, take stock, and to chart the course for the future of this important industry. Here’s where I see the industry headed:

- Regulators will see that earned wages are just your money

Any industry-transforming business change typically requires a major technological breakthrough. Otherwise, that innovation would have happened already. On-demand pay is no different.

It is a profound misconception that the novelty or breakthrough in this industry is the act of a consumer getting money before payday. Despite the name “on demand pay” or “earned wage access,” this industry is not about consumers getting money. Let me explain with a more familiar analogy: When you go to an ATM machine and withdraw $100 from your checking account, do you marvel at the fact that you are now holding $100 in cash? Of course you don’t. Getting your own money out of your own checking account is a trivial, mundane, and expected right. It is inherent to a checking account. The thing that is more interesting is how the money got into your checking account in the first place. Now, moving back to our context, the real “product” behind on-demand pay is not the act of receiving money. It is rather how did the consumer even know how much her accessible earned wages were in the first place. That is the product. That is the innovation.

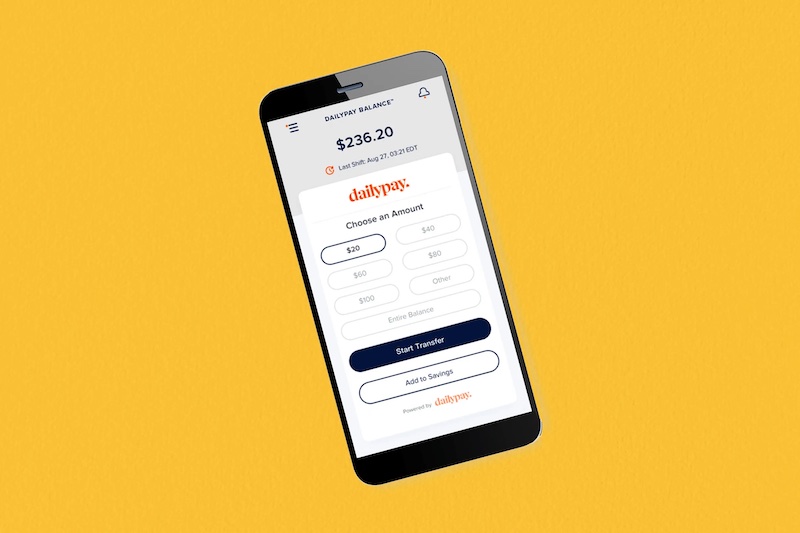

At DailyPay, we called this technological breakthrough the Pay Balance, an entirely new account balance we created. For the first time ever, we could use technology and financial engineering to accurately reflect the amount of net pay an employee had earned. Prior to this, that information only existed in unconstructed data across multiple HR systems of an employer. The canonical technology and systems problem at an employer is that an employer uses one vendor for Time & Attendance and a different vendor for Payroll or the system of record. Additionally, that data was unaudited and unverified during the actual pay period, prior to the payroll processing period at which point the company’s Payroll Department would need to juggle between multiple systems and verify/audit the underlying data in order to run the final payroll for that week.

In order to create an accurate and fully provisioned balance that a worker could rely on as “money in the bank,” one has to figure out how to overcome this data non-interoperability problem and then underwrite the risk that those computations are accurate, while also securing contingent funding to back that Pay Balance. This was an extremely hard problem to solve but thankfully, I worked with brilliant people like Konstantin Getmanchuk (Head of Product) in order to solve it and create an entire industry. It’s why the Pay Balance was named one of Time’s Best Inventions in 2021.

The Pay Balance (Source: DailyPay)

All of that history is meant to provide background to the following truism: the Pay Balance is the consumer’s money, and so any withdrawal from that Pay Balance is analogous to that consumer taking money out of her own checking account. As an example: let’s say an employee has reported she worked eight hours today and is paid $21 per hour. That employee lives in Oregon, has two garnishments for back taxes and child support, and also has a habit of forgetting to clock out for unpaid lunch. In order to establish what her “true” or “net” earnings are for that day, one has to take into account all of those factors on a real time basis. And then in order to make that money available 24/7, one has to underwrite and fund that calculation. That’s really hard to do. But through the leveraging of complex financial technology, one can “create a balance” out of unconstructed data that otherwise does not exist today.

One has to first understand the Pay Balance as a product in order to understand that then accessing a portion of that balance is not a loan. Under no circumstances would any of you consider taking money out of your own checking account to be a loan. I mean, why would you. It’s your money. To be intellectually honest, it’s actually the opposite of taking out a loan. Taking money out of your checking account is a defeasement of a loan that you have actually made to the bank. When you deposit $1,000 into your checking account, you are technically loaning $1,000 to the bank. You are technically a creditor of the bank. The number you see displayed in your checking account balance is technically the money that the bank owes you. And if you withdraw $100 from your checking account, you have reduced the amount that is owed to you to $900.

Now let’s move to one’s earned wages. This is money that is owed to you. Sound familiar? As a worker, you are technically a creditor of the employer. You already have a “pay balance.” It just sits unfunded at the employer in the form of unconstructed data. The technological breakthrough was codifying and consolidating that number into a digital balance, into a digital asset. Then and only then, can the balance be accessed. And just like taking money out of your paycheck is mundane and trivial, taking money out of your Pay Balance is equally mundane and under no circumstances a lending transaction.

Since the Pay Balance is already the consumer’s money, it is most akin to a checking account balance. As such, payments from the Pay Balance are like a consumer withdrawing money from her own checking account, not a loan. Regulatory acceptance of this fact is crucial to continue to expand this much needed benefit to consumers everywhere.

- On demand pay will eventually be offered to 7.8 billion people

While international markets have markedly different payroll regimes, real-time access to pay will increasingly become table stakes across the globe. The expansion of on demand pay into a global offering unsurprisingly started with global companies who offered it to their US employees who want it across their entire global workforce. But it has now expanded to over 100 on-demand pay providers across the globe offering on-demand pay in their respective regions.

I have a front row seat to the expansion of on-demand pay across the globe through my role as advisor to each of the biggest on-demand pay companies in the three major regions around the world. In Asia where there are high rates of unbanked/underbanked, Paywatch has signed up hundreds of employers (and counting) across the region, including in Malaysia, Philippines, Korea, etc. In Europe where monthly payroll is often the norm, Rosaly’s digital offering is helping the 6 out of 10 workers who live paycheck to paycheck. And in Latin America, Payflow is growing exponentially as it signs up the largest employers in the region like Telefonica and Mango. As critical as on-demand pay is in the United States, it is even more essential internationally where payroll cycles, poverty rates, predatory loan rates and banking access tend to be worse. It is exciting to drive on-demand pay from its infancy on each of these continents and to watch these amazing companies fulfill their vision in serving the most vulnerable in their regions.

- The industry will – and must – expand beyond access to one’s pay into long-term wealth creation

At DailyPay, we created the Pay Balance to be a life changing asset for workers. The most valuable property of the Pay Balance is its liquidity. As an asset, what gives the Pay Balance its power is that you can access and spend it instantly like you would money out of your checking account. It’s why millions of people can now stop relying on overdraft and payday loans to pay everyday bills, saving over $600 per year on average. This is the power of leveraging financial technology to create and distribute a new asset.

At my next company Salt Labs, we’ve created an asset to enable workers to move beyond their paying bills. If the Pay Balance is the hourly worker’s Checking Account, her Salt Balance is her Savings Account. At Salt Labs, our technology produces an asset whose greatest property is its non-fungiblity, or its non-transferabilty. The difference in names of the products – Pay Balance versus Salt Balance – fully captures that difference. Your pay is something you should be able to access immediately. Your Salt is not. Your Salt enables savings because its very nature is that it is not spendable on Day 1, but rather preserves your work for the future.

The Salt Balance

There is an escalating savings crisis for low and moderate income workers, which impacts families, communities and workplaces. One can observe this at every level of the savings spectrum. Workers can’t save for the short term: Workers making less than $60k have an average savings rate of negative 2%, leaving nothing (or negative amounts) for unexpected expenses or a discretionary purchase like a present for a relative’s birthday. In the medium term, a staggering 81% of American households report being worse off than 12 months ago. In the long term, the median retirement account value of the 65+ age bracket is zero (thanks to the top quartile, the average is $176k; otherwise it would be negative). Despite four decades of expanding 401(k) access, two-thirds of low and moderate income workers cannot afford the upfront contributions because of the inability to reduce one’s paycheck today for the future.

The future of on-demand pay is in leveraging the best of its offering – access, instant, transparency, and simplicity – and to apply those product properties to the next stop in the employee’s journey – savings and wealth creation. An employee’s financial goals – and by extension, the technology made available to them – must take the employee to get beyond the paying of bills. While critically important, the next part of the employee’s journey is building savings, financial health, and accomplishing medium to long-term goals.

As a financial technology industry, we have an opportunity – a responsibility even – to radically impact the long-term financial health of an entire generation of workers. I take that calling extremely seriously.

Who’s with me.