In an increasingly real-time society, access to earned wages beyond the traditional first and 15th of the month seems like a relatively small ask.

Advancements in technology have allowed payroll, initially complicated and expensive to execute, to become more efficient, soothing pain points and automating the flow of wages. Now, many are questioning the need to conform to traditional time constraints.

Banking is perhaps the last piece in an increasingly rapid economy. For some time, instant access to information and services has been at humanity’s fingertips for a fraction of the price.

Reportedly determined according to the time taken for a courier to travel between European cities, the financial system has a history of long clearing times. Technological advancements have slowly reduced these times, despite the banking system’s lethargy to conform to 24/7 living.

“Today, we can move money in near real-time,” said Phil Goldfeder, CEO of the American Fintech Council. “So creating that optionality for employees who want access to the funds they’ve already earned is a natural evolution for finance.”

“With financial innovation, we’re no longer bound by the traditional legacy challenges, and financial services, using responsible innovation, can provide the consumers access to their funds in real-time.”

Earned Wage Access (EWA) has risen to address this need, allowing citizens much-needed access without reaching for the traditional payday loan.

EWA is not a payday loan

The distinction between EWA and payday loans is critical.

Unlike short-term, high-cost payday loans with steep fees and high-interest rates, EWA has developed to provide employees access to the wages they have already earned.

Split into B2B and B2C solutions, employees can pull on their accumulating wages at points outside the traditional first and 15th of the month. In B2B structures, employees cannot access more funds than they have accumulated. With their consumer-facing counterparts, proof of employment is required, and accounts are repaid when the employees’ regular payroll is released.

Users can either pay a monthly subscription for the service or pay according to transactions. This can be a percentage fee or a “free” service with “tipping” optionality.

Most importantly, its current status as a solution not defined as credit has allowed providers to offer an option to a previously underserved population.

Credit checks are not required, nor do late payments incur penalties on the customers’ credit scores. Late fees and debt collections are also not a feature. The transaction amount is simply deducted from the employee’s paycheck or debited from an employee’s account.

The definition of EWA as a financial solution that sits aside from credit has been an area of focus. In a recently proposed shift by the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) to accommodate the new financial tool, it is referred to as a form of credit, a term The American Fintech Council (AFC) has been eager to counter.

In an open letter to the DFPI sent in mid-May 2023, the AFC requested additional clarity on a credit license exemption to create standards as to which EWA companies could be structured. The organization stated that the solution’s treatment as a loan could affect its ability to provide a service that differs from existing credit options.

“The need for clarification that EWA is not a loan or credit product is fundamental,” read the letter. “Regulations clarifying that EWA is not a loan helps ensure these protections are continued, and the product is as affordable as possible.”

The nebulous ‘tipping’ system

However, this fee structure may be one of the more dubious areas of the sector.

While many earned wage access platforms operate with a subscription fee or percentage commission on transactions, others have implemented a “free” service in which customers can “tip” the company for their service.

The opportunity to tip is integrated as either an opt-in or opt-out feature, where the percentage amount of the transaction can usually be adjusted.

In many of the tipping formats, it is stated that the “tip” is meant to maintain the upkeep of the service and would not necessarily be shared with the provider’s employees. According to research conducted by the DFPI, whether users opt to tip does not affect their access to the service.

The U.S. tipping culture forms a large part of the economy, with many individuals relying on tips generated by good service as a large part of their income. Tipping the good service of an individual seems intuitive in the modern day. However, tipping a financial service system made primarily of code meant to run consistently regardless of any human interaction could be too far.

According to the DFPI’s research, “In 2021, for the 5,827,120 transactions completed by tip-based companies, providers received tips 73% of the time.” Their study focused on five EWA providers, three of which were tip-based and two that were not.

The study found that the average tip amount was $4.09 when the consumer provided a tip. Most advance amounts (80%) are between $40 and $100, with 51% between $80 and $100.

Tips reportedly generated $17.55 million in revenue, while optional fees generated $6.24 million. Companies that did not operate a tip structure were found to have generated $4.31 million in revenue.

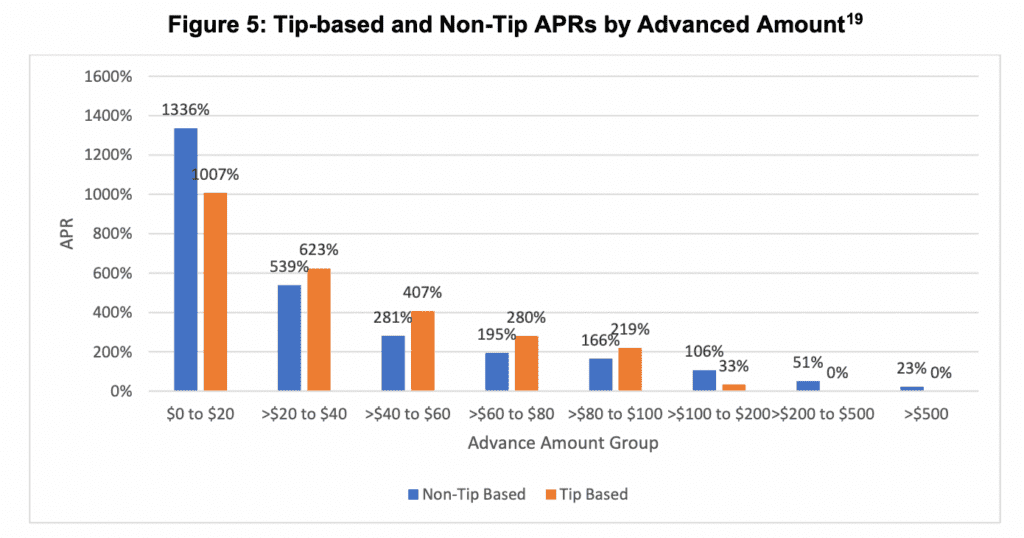

“The average APR for the three tip-based fee structure companies was 334%, ranging between 328% and 348%,” read the report. “The average APR for the two non-tip fee structure companies was 331%, ranging between 315%-344%.”

The study also found that higher APRs were paid by those customers accessing small amounts of earned wage, generally between $0-$20. Those who accessed over $200 in tip-based structure chose not to leave a tip.

The primary issue with the tip structure is that, in many cases, whether the tip is opt-in or out is unclear. Some providers operate tipping systems that add a 10% tip to the customers’ transactions unless they reduce the tip amount to zero. In times when customers are rushed or distracted, this optionality could result in a hefty fee for an already vulnerable individual.

The AFC’s work to build regulated options

Tipping technological systems aside, EWA has become a valuable resource for underserved employees requiring access to funds before their standard payday. As such, the AFC has been working to create standards that allow for innovation while implementing customer protection.

“Unfortunately, there are some companies that are going to take advantage of consumers in need,” said Goldfeder. “So for members of the American Fintech Council, who are in the earned wage access space, we operate with a set of standards to protect the consumer and work within a regulatory structure that already exists.”

“The goal is to look at the existing regulatory structure and figure out how to maneuver best to ensure that we’re able to offer innovative optionality for consumers without compromising consumer protection.”

Already, the AFC has worked with regulators to respond to the BNPL space. The sector, previously hung with the controversy around a lack of transparency of late fees and impacts on credit scores, has since blossomed into an industry assisting many previously underserved customers in accessing credit.

“Those standards are still being built out for the nascent EWA industry. But we’ll have a better answer as the industry matures and we recognize and understand how consumers utilize the products. And we’re better a more direct answer to what those standards look like.”

For Goldfeder, while the AFC continues to work with regulators to define these standards, transparency will be the bedrock.

“Consumers need to understand exactly what they’re getting and what it’s going to cost them,” he said. “Transparency is critical.”

RELATED: