The aid world’s drastic reconfiguring may have profound long-term effects on what makes for common sense within the fintech sector.

It all came to a grinding halt three months ago. On January 27, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued a “temporary pause” on “all activities related to obligation or disbursement of all federal financial assistance.” Among other consequences, the announcement rendered the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) a shell of the $40-billion-plus entity buttressing global aid flows it had been just weeks before; more than 5,000 workers have lost their jobs, aid has slowed to a trickle, and a slew of unions, advocacy groups, and other entities have turned to the courts in an attempt to mitigate or undo the damage (with mixed results).

“We spent the weekend feeding USAID into the wood chipper,” head of the pseudo-governmental Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), Elon Musk, wrote on February 2nd.

These sudden cuts have already proven fatal. Reporting by the New York Times recorded the deaths of HIV-positive children in South Sudan arising from the sudden interruption of US-administered HIV prevention and treatment programs, and suggested that more than 1.6 million people could die in the coming year if these programs do not resume. Millions more people could die if other disease prevention, vaccination, and food aid programs wither away.

Why are we covering the decline of USAID in a fintech publication, beyond, for many, the existential stakes involved in sudden disruptions to the aid world, despite its myriad flaws? Telescoping out from a handful of technologized institutions playing a role in disbursing capital where it’s acutely needed to presently save lives: The aid world’s drastic reconfiguring may have profound long-term effects on what makes for “common sense” within the fintech sector. Many of fintech’s most enduring (if justifiably controversial or concerning) ideas have incubated within aid-reliant environments and have benefited from top-down coordination. Think microfinance, M-PESA, UPI, and other major infrastructure or approaches to debt, payment, and finance. What does the interruption of information-collection, engagement, and assistance mean for future waves of technologized proliferation, if they arise?

While the future of USAID’s programs is battled out in public courts as well as Beltway-insider antechambers, aid-sector participants have scrambled to mitigate the damage of USAID’s dismantling — often using financial technologies and extant private-sector diligence frameworks to expedite the collection, monitoring, and disbursement of capital to aid programs that save lives.

“To a significant extent, before the USAID freeze, there was already [a dire situation] in terms of funding for the most cost-effective stuff,” said Matt Lerner, Managing Director of Research at Founders Pledge. The nonprofit connects entrepreneurs to charitable-giving opportunities funded by the proceeds from their exits, and has transferred more than $1.5 billion to the charitable sector. It counts the founders of Wise, Klarna, Kabbage, and other major fintechs as members.

Lerner said anti-malarial efforts are a “canonical example” of an issue that already had “billions in room for funding” before the USAID freeze. “The situation was an emergency before that nobody was talking about, and now it’s more of an emergency that people are talking about,” he said.

The evaporation of billions of dollars in funding has compelled Founders Pledge — as well as other entities — to establish emergency funds helping programs survive the short-term jolt of USAID’s dismantling. In partnership with charity evaluator The Life You Can Save, Founders Pledge has raised over $3 million through its Rapid Response Fund, which aims to “help prevent a catastrophic loss of progress in global health, extreme poverty, and humanitarian aid.”

“It’s a lot of money to a lot of people, but also it’s .001 of the required sums,” Lerner added.

According to Jessica La Mesa, Co-CEO of The Life You Can Save, the Rapid Response Fund had a head start over similar initiatives because the Fund prioritized organizations with pre-existing connections to The Life You Can Save — hopping over the minutiae and compliance requirements involved in cross-border payments.

“We’ve already done the diligence. We’ve already done the financial controls. We’ve already been granting them money, and have processes in place to know that the money arrives to where it’s supposed to,” she said.

That’s different from the approach undertaken by Unlock Aid, a coalition of researchers and organizations tackling policy-first changes to global aid systems. Following the OMB’s announcement, the organization quickly set up its Foreign Aid Bridge Fund to distribute capital to organizations in urgent need of funding. The organization received more than 600 applications and stood up a volunteer investment committee to determine how to distribute funds.

Walter Kerr, Co-Founder of Unlock Aid, told Fintech Nexus in early April that the Bridge Fund had raised $1.85 million from almost 500 individual donors and small family foundations. It’s raised funds through the platform Every.org (founded and partially funded by Uber co-founder Garrett Camp), and uses Seattle-based philanthropic infrastructure solution Panorama Global for diligencing and payment distribution.

In an interview with Fintech Nexus, Every.org President Allison Fine said it took two hours to set up fundraising rails for the Bridge Fund, enabling the Fund to accept cryptocurrency, mobile payments, credit card payments, and other modalities. Every.org uses Stripe to power these capabilities.

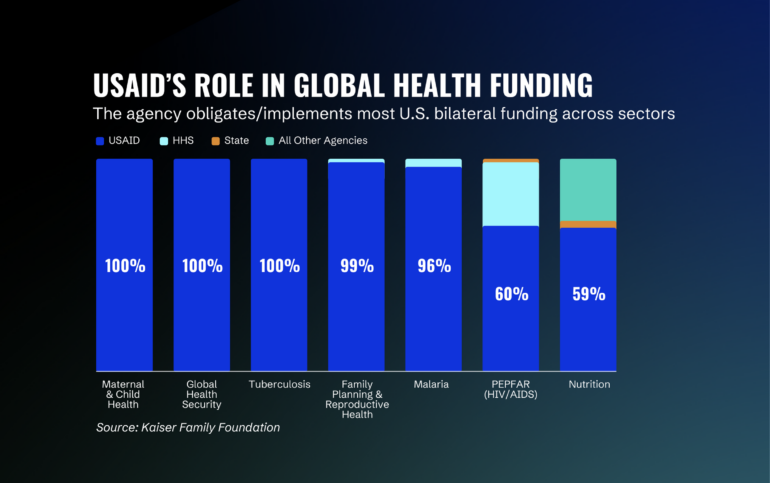

But, as these various private-sector fintech-driven initiatives acknowledge, they’re often using the vestiges of USAID information-gathering to determine how to (very) partially fill in the gaps. Prior to the January OMB order, USAID functioned as a keystone mechanism to identify geographies in need of aid, and coordinated billions in related disbursements.

“Big complex international aid programs [like HIV prevention and treatment program PEPFAR] are things that the US government really only has the capacity to administer,” Lerner of Founders Pledge said. “That administrative infrastructure is now seemingly kaput.” In response to these new dynamics, more discrete and administratively straightforward programs are more likely to receive private-sector funding, at least in the medium term. A certain subset of areas are more likely to receive funding too — those with more quantitative returns, like medical intervention, rather than qualitative concerns, like capacity building.

Granted, part of the reason for this vacuum is a question of history. USAID moved away from aid work itself and became a coordinator and contractor. Former USAID Deputy Administrator Carol Lancaster said in 2009 that “USAID has left the retail game and become a wholesaler. In fact, it’s become a wholesaler to wholesalers.” That pivot partially explains USAID’s deep ties to major payments networks and other private-sector participants: partnerships with the likes of Visa and Mastercard, as well as initiatives supporting dozens of digital finance service providers.

Beyond the scope of this article, which highlights fintech-dependent players responding to the USAID-induced crisis in aid, are additional questions answered by a litany of historians and practitioners: the questions of how aid frameworks came to be and their relationships to extraction and colonialism, the moral and political questions involved in the private-sector evaluation of need and disbursement of aid, and the question of where to go from here. Extrapolating, we might conclude that the US’s public-sector retreat from financial coordination and information collection within the world of global aid may ultimately slow the spread of modern fintech solutions that trace their origins to foreign markets. Fed into the wood chipper.